The East Wind Blows Westward

How digital editing, deepfakes, and data filters rewired the old machinery of state censorship

In a cramped Prague basement in the late 1970s, the clatter of a battered typewriter ceased after every two strokes so its ribbon would not jam while punching through carbon paper. My father, then in his early twenties, collected three smudged sets of pages, bound them with thread, and passed the handmade paperbacks among friends. The title was not a banned manifesto but Pán Prstenů—the Czech samizdat translation of The Lord of the Rings. During Communist rule, even fantasy novels moved only through clandestine networks; carbon paper yielded at most fifteen legible copies, and every typewriter ribbon was registered with the secret police.1

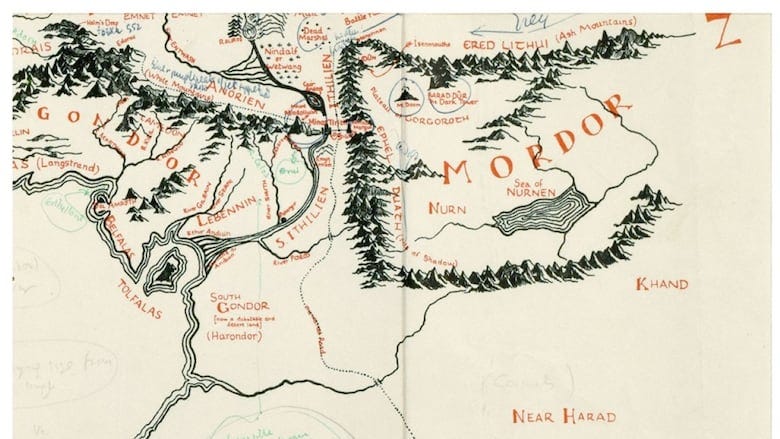

Why did a regime fear hobbits and wizards? Party censors noticed that evil in Tolkien’s epic emanated from the East (Mordor) while hope gathered in the West. As the trilogy’s Czech translator later recalled, a saga of “small peoples uniting to take on an Evil Empire in the East” was “politically unacceptable” to officials who heard an echoed Cold War geography.2 A total ban was a blunt instrument, but it spared the regime the cognitive dissonance of seeing Gandalf march eastward in a state-approved rewrite.

Half a century later, the Chinese Communist Party perfected the subtler tactic that Moscow never attempted: surgical editing. When David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999) finally streamed on Tencent Video, Chinese viewers saw no collapsing skyscrapers. Instead, a black screen announced that “the police rapidly figured out the whole plan and arrested all criminals,” while Tyler Durden was confined to a mental hospital.3 Hollywood spectacle remained, but its moral was inverted: the state triumphs, the anarchists lose.

Digital tools have multiplied the censors’ reach. Automated filters screen billions of posts per day, opaque recommendation engines quietly bury dissent, and privately owned platforms perform what scholars term “algorithmic censorship,” exercising “an unprecedented degree of control over both public and private communications”.4 Propagandists, meanwhile, have gained an equally powerful offensive weapon. Google’s new text-to-video model, Veo 3, can fabricate convincing clips of riots, election fraud, or wartime atrocities; investigators warn that its watermarks are easily stripped, leaving “hyper-realistic deepfakes that can spread misinformation and incite unrest”.5

What can be done? Transparency reports and independent audits can expose covert edits and algorithmic biases. Media-forensics standards such as C2PA aim to cryptographically link authentic footage to its source, while robust digital-literacy curricula must train citizens to spot splicing, trace provenance, and resist emotional manipulation. Finally, narrow, content-neutral laws—targeting demonstrable harms such as non-consensual deepfakes or coordinated foreign manipulation—offer a sturdier safeguard than ideology-based bans.

Prague’s basements have yielded to cloud servers, and carbon copies to neural nets, yet the struggle endures. My father’s clandestine paperbacks remind us that stories are worth the risk; they can inspire solidarity even when reproduced only a handful of times. In 2025 the danger is not scarcity but surplus: separating truth from synthetic noise. Whether wielded by states, corporations, or lone hoaxers, modern censorship and propaganda still seek to shape reality by controlling the stories we tell. Our task is to keep the presses—physical or digital—open, so that when future readers seek The Lord of the Rings, they find Tolkien’s words intact, not repurposed to serve a new Sauron.

“History of Samizdat in Czechoslovakia,” Libri Prohibiti entry, Wikipedia (accessed 6 June 2025).

Sean Hanley, “Comrade Baggins? When Middle Earth Met Middle Europe,” Dr Sean’s Diary, 29 Dec 2014.

“Chinese Streaming Service Changes the End of Fight Club so the Police Win,” TIME, 25 Jan 2022.

Jennifer Cobbe, “Algorithmic Censorship by Social Platforms: Power and Resistance,” Philosophy & Technology 34 (2021): 739-766.

Billy Perrigo, “Google’s New AI Tool Generates Convincing Deepfakes of Riots, Conflict, and Election Fraud,” TIME, 3 June 2025.