Why I Donate All of My Book’s Proceeds to the Nonprofit Girls Who Code

Honoring the legacy of women pioneers in computing

Standing before the Harvard Mark I Computer in our university’s Science Center, I was struck by the contrast—its massive 8-foot frame and intricate mesh of wires and switches commanded the room, yet my classmates strolled past with barely a glance. This technological colossus, once the crown jewel of the U.S. Navy’s computing arsenal, now stood as a silent sentinel of innovation. The irony wasn’t lost on me: the computational power that once filled a room in the 1940s now fits comfortably in our pockets, thousands of times more powerful. What my peers failed to appreciate was the legacy hidden within this mechanical giant—not just the engineering marvel itself, but the pioneering women programmers whose groundbreaking work paved the way for modern computing. In this seemingly obsolete machine lies the DNA of our smartphones, laptops, and the digital conveniences we now take for granted.

As a history-enthusiast-turned-computer-geek, I found the allure of early computers, like the Mark I, irresistible. These groundbreaking machines enabled inquisitive minds to wield unprecedented power, crunching complex calculations that shaped the atomic age and propelled humanity to the lunar frontier. The limitless potential of programmable machines, though evident in retrospect, required visionary individuals to look past the imposing hardware and envision something more than just an advanced calculator. The ingenuity, tenacity, and achievements of these trailblazing technology pioneers brought the promise of general-purpose computing to life. It was their inspirational journey that fueled my passion for computer science.

History’s first coder, Ada Lovelace, was a woman. Through her correspondence with the British mathematician Charles Babbage, Lovelace discerned the boundless potential of his invention, the Analytical Engine, and conceived what is widely considered the first-ever computer algorithm.1 Regrettably, Babbage’s groundbreaking invention remained unfinished, and nearly a century would pass before the world witnessed machines akin to his and Lovelace’s visionary concept. Among these technological marvels was the Mark I, standing as one of the world’s first general-purpose computers.

Drawing inspiration from Babbage’s Analytical Engine, the Mark I melded mechanical and electronic components in its innovative design. The construction spanned over five years, and upon its delivery to Harvard University in 1944, the computer was swiftly enlisted in the war effort. Among the first coders to operate the Mark I was Grace Hopper, a mathematics Ph.D. and U.S. Navy recruit. Dr. Hopper and her team harnessed the machine’s capabilities for various military projects, from torpedo design to implosion computations vital to the atomic bomb’s development.2 It was a somber reflection of the times that the Mark I—a testament to human ingenuity and a harbinger of today’s digital revolution—initially served destructive ends. Fortunately, the war’s end soon ushered in a new era of civilian applications for programmable machines, with Dr. Hopper at the forefront of this transition.

After the war, Dr. Hopper continued to play a pivotal role in the nascent field of computing. In the 1950s, she developed one of the most significant innovations in software engineering: the compiler.3 As an intermediate program that translates human-written code into machine instructions, the compiler revolutionized programming by enabling software creation in plain English instead of arcane machine code. Dr. Hopper also co-developed one of the most popular early programming languages, COBOL, which remains in use in production systems to this day.4

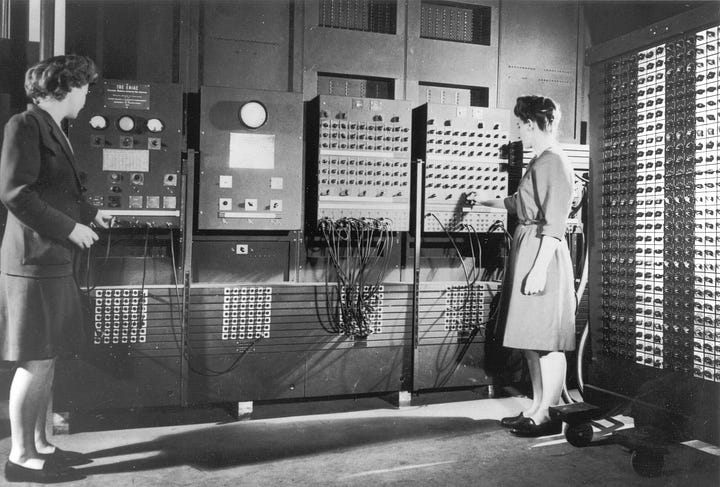

Dr. Hopper’s story is far from unique; the annals of computing history are filled with trailblazing women whose dedication and ingenuity helped propel humanity into the digital age. The monumental task of programming the ENIAC, the world’s first fully digital general-purpose computer, was accomplished by an all-female team: Kathleen McNulty, Jean Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Frances Bilas, and Ruth Lichterman.5 Unlike its electromechanical predecessors like the Mark I, the ENIAC was entirely electronic, which enabled it to achieve unprecedented computing speeds. While the Mark I could execute a mere three commands per second, the ENIAC boasted a staggering five thousand in the same timeframe.6 This breakthrough helped meet the burgeoning computational needs of the American war machine, but it also rendered traditional coding methods obsolete. New paradigms had to be devised to harness the power and complexity of the novel hardware. Undaunted, McNulty and her colleagues pioneered techniques such as subroutines and nesting, thereby laying the foundation for contemporary software engineering.7

As computers transitioned from instruments of destruction to household staples, women programmers remained at the vanguard of software innovation. In the 1960s, Mary Allen Wilkes was entrusted with developing the operating system for the LINC, widely regarded as the first personal computer due to its compact size. In contrast to its colossal, multi-ton predecessors, the LINC was small enough to fit within a single lab or office. Wilkes even brought the machine home, making her the first person to use a personal computer.8 The LINC’s revolutionary design extended beyond its dimensions. It featured a screen and keyboard, enabling direct and interactive programming—eliminating the need for punch cards and printouts required to operate earlier computing machines.9 Wilkes’s trailblazing programming contributions during her work on the LINC laid the groundwork for contemporary operating systems, from Windows to iOS.

Women programmers also played a central role in NASA’s space program, adding a touch of irony to Neil Armstrong’s iconic phrase. Dorothy Vaughan, a self-taught FORTRAN programmer, along with her female colleagues, carried out many of the computations that facilitated the first American’s journey into Earth’s orbit and ensured a safe return.10 Another prominent computer scientist, Margaret Hamilton, led the engineering team whose software powered the historic Apollo 11 lunar mission.11 In light of these invaluable contributions, Armstrong’s famous words, “one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” inadvertently overlook the vital role these pioneering women played in achieving that monumental milestone. Regrettably, the contributions of these trailblazers often remain under-appreciated or even forgotten.

The prominent role women played in the early days of software engineering contrasts sharply with the makeup of today’s computer science classrooms and workplaces. According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, women earned only 27% of computer science bachelor’s degrees in 1998; by 2018, this figure had dropped to below 20%.12 In the tech industry, women held around 27% of computer and mathematical occupations in 2022, as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.13 The gender disparity cannot be attributed to any inherent lack of aptitude. The groundbreaking accomplishments of female computer scientists serve as undeniable evidence that success in computing knows no gender.

In recognition of the remarkable accomplishments of the programming pioneers discussed in this essay, I am proud to support the nonprofit organization Girls Who Code. As a young history enthusiast with a passion for technology, I found inspiration in the trailblazing women coders; their stories and accomplishments led me to pursue a degree in computer science. I am honored to pay it forward to future generations of female technology leaders by donating all proceeds from my book, GANs in Action, to a nonprofit committed to addressing the gender gap in technology. This modest contribution pays tribute to those who came before and helps empower the upcoming innovators who will continue to shape our digital world.

An earlier version of this article first appeared on Medium in 2019 in Towards Data Science.

Harvard Mark I, introduced by Prof. Harry Lewis

C. Thompson, The Secret History of Women in Coding (2019). The New York Times.

Harvard IBM Mark I: What was it used for? (n.d.). The Harvard University Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments.

Harvard IBM Mark I: The Crew (n.d.). The Harvard University Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments.

Ibid.

C. Thompson, The Secret History of Women in Coding (2019). The New York Times.

W. Isaacson, Grace Hopper, computing pioneer (2014). The Harvard Gazette.

J. Lightfoot, Introducing ENIAC Six (2016). Atomic Object blog.

C. Thompson, The Secret History of Women in Coding (2019). The New York Times.

Ibid.

E. Howell, The Story of NASA’s Real “Hidden Figures” (2017). Scientific American.

A. George, Margaret Hamilton Led the NASA Software Team That Landed Astronauts on the Moon (2019). Smithsonian Magazine.

Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering (2022). National Science Foundation.

Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (2023). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.